First published on November 2011.

The revolution is being televised: every day in the news we see radical changes being enacted around the world. It is also being digitised, and people are finding new ways of doing things for themselves. Two areas where change is happening at a frenetic pace are in the education system (in its broadest sense) and the creative economy. This collection takes a look at where these two fields meet, and how they interact.

In the introduction to his 1999 report for the government ‘All our futures: creativity, culture and education’ Ken Robinson wrote ‘Education throughout the world faces unprecedented challenges: economic, technological, social and personal… We argue that this means reviewing some of the basic assumptions of our education system’.

Twelve years on, with hundreds of billions expended, much legislation passed, and another entire generation of young people having passed through our education system, there’s not much evidence of that shift in assumptions. If anything, the response from this government, as from the last, has been to cling tight to the oldest and most entrenched of our collective assumptions about education and learning – literacy, numeracy, narrow targets, exams and discipline – all eminently suitable for Mr Gradgrind’s empty vessels. Even the term ‘apprenticeship’, suddenly re-invigorated, has a reassuringly well-worn, Victorian, feel.

None of it acknowledges the profound changes sweeping through our world. It’s worth recalling J K Galbraith’s observation on how governments and bankers responded to the Wall Street crash of 1929 – ‘Faced with the choice between changing one’s mind and proving that there is no need to do so, most people get busy with the proof.’

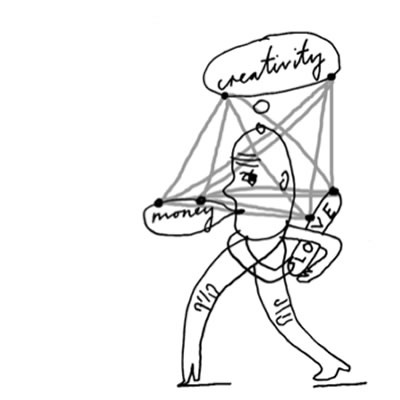

As the title of this book suggests, our premise is that we have allowed concepts and values that belong naturally together to become divorced. Creativity, money and love is our shorthand expression for the things we all need and want to be able to lead fulfilling lives. Learning how to engage with them, value them and keep them in some kind of sustainable balance must be at the core of what each generation seeks to pass on to the next. It is what keeps our societies dynamic and harmonious. Therefore they each demand some place, some recognition, in the structures we put in place to educate our children and to pass on the skills we go on acquiring throughout our lives. This should not be a radical proposition because we instantly recognise it as true. Yet we fail to put it into practice.

So where do we start? A good place to begin is with the skills needed for the creative and cultural industries because they are, in so many ways, harbingers of the future. Because so many of the creative industries are riding the digital wave, indeed are dependent on it for their existence and part of the energy that drives it, it is in this sector that many of the problems and opportunities that are beginning to impact on every part of our society are most apparent. And because so many of the creative industries are at the interface of economic activity and cultural activity, because they engage people at the most visceral personal level and at the most potent social level, their strengths and weaknesses can provide a glimpse into what the future holds for much wider swathes of our society.

Across the world culture is playing an ever-increasing role in people’s lives. There are millions more users of the internet and social media every month, where much activity is culturally driven. More and more people are making a living from culture, and politically, it is often cultural activists who are leading protests from Tahrir Square (so that they can change their government), to Kensal Rise (so that they can save their public libraries). All of a sudden, the UK Department for Culture Media and Sport has found itself transformed from being the smallest, most marginal department in Whitehall to being at the centre of two of the biggest news stories of the decade: one about criminality and regulation in the media, the other about the consequences of riots for the London Olympics. Cultural questions are now at the heart of change, and the interconnectedness of creativity, money and love is becoming ever more apparent.

The creative sector has been a significant contributor to economic growth (it is said to account for 7% of the UK’s GDP) and social innovation. As a nation, and as individuals, we need to be able to make the most of the economic and social opportunities that creativity and culture offer.

We need an education and training system that is fit for purpose in the age of creativity. We need public and private sectors to be working together to make a better future.

The Prime Minister recently installed a Tracey Emin piece in Number Ten. It is a neon sign that says ‘More Passion’. We agree, because the stakes are high. We have invited passionate responses from a wide range of people from different disciplines, places, and viewpoints to the broad question: What does the education and learning system need to look like for people to lead creative lives and so that the creative and cultural industries flourish?

Creativity Money Love: Learning for the 21st Century by Creative & Cultural Skills is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

Creativity Money Love: Learning for the 21st Century by Creative & Cultural Skills is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

Illustrations by Paul Davis - http://copyrightdavis.blogspot.com/