First published on November 2011.

For the creative industries to thrive, from the first scribblings at playgroup, to the most sophisticated innovations of our Masters students and beyond, we must ensure that all those with the innate talent and potential are able to access careers in our sector and flourish.

Whilst there are any number of things that might be done to improve the experience our proto-creatives have in classrooms and studios as they progress up the chain, for far too many, they will never even set off down the path. Parents up and down the country have advised their children (probably in the millions) not to study the arts as it offered no secure or fiscally rewarding careers even after years of dedication – the trouble is that they’re both right, and our entire sector conspires to continue to make this the case.

It is now broadly accepted, and experienced, that the creative industries ‘recruitment’ methodology relies upon an extended period of unpaid work (in practice, entirely illegal by even the most basic of minimum wage law interpretations). The impact of this and the aura of low-pay or even no-pay in the sector is such that (even based on pre-recession figures) Arts graduates can expect an earnings premium of less than £35,000 over an entire lifetime, compared to their peers with no equivalent qualifications. Factor in the actual cost of the education to date, and the average creative doesn’t just fail to benefit fiscally from years of training, their livelihoods will actually be damaged by it.

The tragedy of this is lost on too many creative industries employers. They cite interns that spend a few months cutting their teeth at various companies, who enjoy the experience enormously. These overwhelmingly middle-class interns may then go on to enjoy a career where they will earn less than they could in any other sector, perhaps going on to exploit more unpaid workers in the misguided belief that because they learnt this way, their successors should too.

Any creative endeavour is a business. An arts employer is still an employer. They must accept the responsibility that all businesses in this country accept: they must make enough money to pay their employees the legal minimums. The cost of this is passed onto the person buying theatre tickets, paintings, or whatever their product is. If there is no market to pay for the business to operate legally and pay its staff, it is entirely legitimate that business should not survive.

Businesses that do not pay legal minimums are competing unfairly with legitimate employers who are following the law. This unfair wage practice inevitably suppresses the value attributed to our labour, and produced the bizarre range of models for wages (or lack thereof) we see today – from actors promised ‘profit shares’ to the systematic abuse of ‘internships’. Employers must be held to account for destroying markets like this. It is a vicious cycle which undermines the health of the sector, and in many cases creates a dependency on subsidy.

How can our education system change to support the creative industries? Right now the first criteria for participation in the arts is an ability to work for free. Imagine how competitive our sector would be if the criteria was talent.

¬Ý

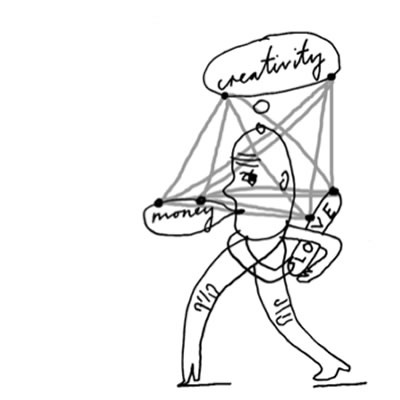

Creativity Money Love: Learning for the 21st Century by Creative & Cultural Skills is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

Creativity Money Love: Learning for the 21st Century by Creative & Cultural Skills is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

Illustrations by Paul Davis - http://copyrightdavis.blogspot.com/