First published on November 2011.

I remember little of what I was taught during my formal education. All those facts and figures learned by rote, gone. However, I do have an uncanny memory for almost every film, book, song and anecdote I watched, read and heard during that period. This isn’t because I was a bad student. On the contrary, I was one of the lucky ones. I could cope with sitting for hours as various teachers pointed out a set of facts entirely unrelated to the previous set dispatched 45 minutes earlier.

Being a lonely child may have fuelled my love of narratives. I’d draw the curtains to protect the TV from the sun’s glare and bask in the luscious world of a Hollywood matinee. I was last to bed after puzzling my way through a Friday night French film. I read everything in the Reader’s Digests left lying around. I eavesdropped on my family’s swapped memories of the Caribbean. Like most growing teenage girls, I’d religiously tape the Top 40 every Sunday and listen over and over to the stories within the songs.

Nobody knows where my Johnny has gone.

Judy left the same time.

What made me such an avid consumer of stories? Simple. It was a search for meaning. Childhood years, especially teenage ones, are the most tumultuous we’ll experience. The rapid development between 10 and 16 takes place over a short-six year roller coaster ride. It’s a crazy, confusing hormonal soup of a decade over which the narcissistic haze of childhood recedes to reveal our perceived places in the world. No wonder we rebel.

Stories are as important to our newer generations as ever. A Nintendo DS might have replaced a Reader’s Digest but the imperative is the same. Video games allow people to experience life as an Odysseian hero while our real world offers us few such options. Young people who are most caught between rocks and hard places are our greatest dreamers. They have to be. They throw themselves into new realities through the music they make in their bedrooms and their personas on social networks.

Call them what you will – stories, hypotheses, experiments, rumours – these are the mothers of invention. Every new economic, social, political and personal development is a story created. Story makers play with potential routes and outcomes, monitor variables, cross out and rewrite. They are aware of risky dead ends but have faith in their ability to find alternate avenues.

True innovators are curious enough to challenge and test the narratives that already exist. They understand that such stories are man-made and therefore can be man-unmade. (Is it really true only Etonians are fit to govern the country while a life of criminality awaits council estate dwellers?)

They are rigorous with their research and take seriously their responsibility, aware that an established narrative can create a measure for people’s actions.

Surfing the online and offline world, it is clear that the desire for creating and sharing stories has not diminished but we seem to be facing a crisis of meaning. It is here that the true untaught power of stories lies.

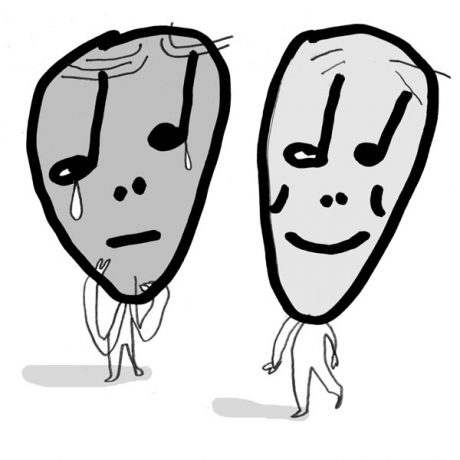

Stories teach us perception. They not only help us understand the world we inhabit but influence the world we go on to create. They instruct our emotional triggers and affect whether we approach our futures with confidence or dread. Most importantly, we can just as easily teach young people that they can create a whole new narrative path for their lives and their world, than accept the story they have been given.

But without understanding how to do that ourselves, without taking the risk to redraft our own stories, how do we expect young people to be so enlightened? How can we ask young people to develop a set of deeper values if we clog the narrative airwaves with hundreds of hours of Katie Price, money-obsessed pop artists and vacuous teenagers from Jersey to Geordie Shore. Adults lamenting the soullessness of young people is a little rich (excuse the pun) when it is adults, not children, that commission, inflate, fabricate, hack and greenlight such bleak stories.

Art can help us understand the complexity between meaning and message. It makes us viscerally aware of how our external environment impacts our internal perspective. It can help us reflect on consequence, (hi)stories and responsibility. This is what Tony Benn meant when he said in an interview that it is the work of artists that will survive, not the work of politicians.

We, adults, need to take much better responsibility for the stories we hand to our young ones. We need to begin sharing stories of compassionate heroes as demonstrated in the work of filmmakers Abderrahmane Sissako and Thomas McCarthy. We could better contemplate the moral complexity of choice aided by the work of debbie tucker green or reflect on the grace of humanity as demonstrated in Lynne Ramsay’s Ratcatcher. But first we must choose to kindle those aspects within ourselves. You see, the real potential of a creative education is not to train artists to make a living but to train those living to redraft our worlds as creatively as artists.

Creativity Money Love: Learning for the 21st Century by Creative & Cultural Skills is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

Creativity Money Love: Learning for the 21st Century by Creative & Cultural Skills is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

Illustrations by Paul Davis - http://copyrightdavis.blogspot.com/