First published on November 2011.

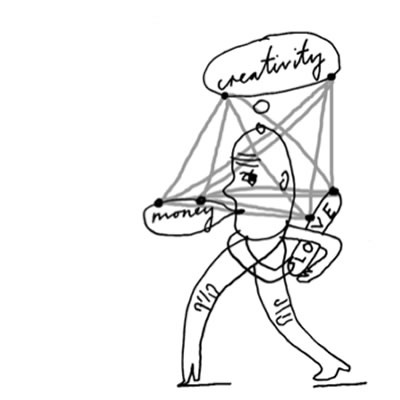

It is not wise to speculate on possible interventions in creative education with assumptions based on a single type of person wishing to engage in the creative or cultural sector as a way of life. Neither is it necessary to avoid such speculation. Rather, one can create a graph relating to temperament, along which such people are ranged and treat intervention according to where on the graph they sit.

At one extreme is the pure creator. Abstracted, unworldly, obsessed, often academically inept, gifted, impractical. The poet, the painter, the composer. Few poets learn to drive a car and if they do they will eventually crash whilst gazing abstractedly out of the window. At the other end is the prosaic arts lover who may have no talent at all for performing or producing art but may be intensely practical, driven, capable, intelligent and appreciative.

Neither of these extreme but vital talents is properly considered by Western education. The pure artist is encouraged (or should we say discouraged?) by educators and commentators pushing the value of skills, entrepreneurship, social networking, business studies and so on. At the other extreme, almost all creative courses in the UK insist on a performing element. For example, you will not find courses in offstage music performance skills which do not require the candidate to play an instrument of some kind. This will exclude the passionate non-creator who yearns to learn practical skills to support performance or creation.

A successful rock band will need the obsessive, truculent, ineducable singer-songwriter who strums a few self-invented chords on an old guitar; the skilled and learned keyboard player and arranger; the solid practical drummer and bass player; and, crucially, the manager – their classmate at school who could not play a single note but who believed his friends were destined for greatness. In this example, the keyboard player, bass player and drummer sit somewhere along the graph not close to either end. They will find endless courses to hone their skills and will most likely appreciate training in enterprise and business, financial affairs, practical maintenance, music arranging and more. All of these skills will not only help the band but will help give these creators a life outside and after the band.

But there is no help for the self-taught singer who plays a few chords on their guitar. They do not need to learn more chords, they do not need to learn how to mend their amplifier – but they may well benefit from voice coaching, theatrical performance skills, creative writing tuition and social interaction: how to give an interview. They will not find a resource to advise them nor a course to assist them. The manager will benefit hugely from business and financial skills, advice on touring, international relations, promotion, being an employer. But they will also benefit from an understanding of lighting, recording, the creative temperament and how to handle it. No such programme exists which allows this crucial part of a good managerial skill set.

We are a long way from understanding how to implement these mixed approaches, but my own view is that a study of the foundation years in further and higher education, seeking input from employers and creators to tune these foundation courses to attract the widest range of those along the graph, is the way to start. Exclude no-one.

Creativity Money Love: Learning for the 21st Century by Creative & Cultural Skills is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

Creativity Money Love: Learning for the 21st Century by Creative & Cultural Skills is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

Illustrations by Paul Davis - http://copyrightdavis.blogspot.com/